A note from Banks Post Editor Chas Hundley: We are expanding our small collection of columns (Banks Police Log, Banks Fire Log, and Dispatches from History) to include this occasional information column from the Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this column belong solely to the author and/or TSWCD staff, not this publication.

An occasional column from the Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District.

By Adriana Lovell, Education & Outreach Specialist, TSWCD

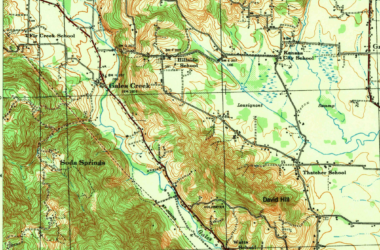

“It wouldn’t be January without high-water signs on LaFollett Road south of Cornelius where the Tualatin River spills over at least once each year.” Or so says a 1974 edition of the Hillsboro Argus, the official Washington County newspaper at that time. Recent history of this stretch of the Tualatin River is a reminder that many of us live in a floodplain1.

Floodplains are an essential part of the river.

Flooding is a normal part of our waterways. Rivers and streams swell with rainwater or snowmelt, causing water to exceed its banks and spread out across the land. This natural process creates wetlands, moves streambanks, and creates the tug and pull characteristic of a dynamic river.

When houses and things that are meant to stay dry are built too close to these seasonally wet places, trouble abounds. Flood control becomes a tool we use to change how and where water moves. In many places we create berms or cement barriers to disconnect the river from the places where it once naturally flowed. Because our river systems are a powerful force of energy, water almost always finds a way back to its natural path.

Allowing lowlands to flood once again is vital for the health and resiliency of our waterways. Floodplains allow for the recharge of groundwater2 for wells in the area and do the work of holding water when we need them to. We must protect these lands as valuable areas to store and filter water, reducing the impacts of flooding downstream.

On a rainy winter day in 2022, decades after the Hillsboro Argus frontpage showed flooding on LaFollett road, water continues to pour out of the river into the awaiting floodplain. A bright line of lichen begins several feet up the trunks of riparian trees. Contrasted by a dark water line, this lichen serves as a visible reminder that severe flooding happens here a lot.

Change is constant when living along the Tualatin River.

For years, the LaFollet Road community has grown alongside the Tualatin River, swimming, trout fishing, pheasant hunting, and catching crawdads. The area includes quiet stretches of fields, remnant old forests, the remains of a decades-old playground, and wetlands inhabited by deer and thousands of waterfowl. The area has the appeal of peaceful rural riverside living with the convenience of urban amenities not too far away in the town of Cornelius.

Many neighbors have lived in the area for decades. They’ve seen the annual floods and recognize it’s a part of living in this stretch of low-lying land along the river. Much of the riverside area is not suitable for farming. Nick Duyck, a blueberry farmer involved in the project noted that more development in the surrounding area means more water is going straight into the river. He’s noticed in the last 30 years the flooding has severely worsened. It’s not unheard of for the water of the Tualatin River to rise two feet in one day.

Neighbors are embracing the floodplains.

Over 70 acres along the river here have existed in various states including manicured lawns, tall fescue grown for grass seed, pasture, and a nursery. Now, with the help of Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District (Tualatin SWCD), landowners in the area have come together to embrace the water, flooding, wildlife, and wetlands.

“The notion of setting it aside for restoration and preservation…that’s a value we all shared” says Chuck Simpson, one of the neighbors involved in the project. “The plus of it being this stretch of neighbors getting together, having it all happen at once, it makes a big difference from an… ecological point of view. You can have real impact on what goes on here. We have lots of wildlife but we’re going to have a lot more.“

Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District looks for projects that are large and connected to increase their impact.

Jason Dumont is another landowner who’s enrolled in the project and is helping to implement it too. He recently relocated his business, Mosaic Ecology, to the area. This environmental restoration firm installs native plants in the tens of thousands across the county every year. The Mosaic Ecology crew is planting willow, pine, oak, native roses, sedges and more. By the end of the project, a total of 52 acres of plant communities will be restored. These new plants will provide year-round wildlife habitat, and play a role in reducing erosion of the streambank, soaking up water, and filtering pollutants3 and excess nutrients and runoff from lands upstream.

“We feel a sense of responsibility to the river and the land to make it better than it was when we came here…We always wanted to restore the wet parts of the property, but didn’t have the financial capacity to do it. Once Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District became involved, they really opened up the opportunity to restore not just the edges of the river, but the ponded wetland areas too. Being able to do things at a large scale, in a coordinated way with our neighbors made a lot of sense. Their ability to fund the work, pay for materials and planning was fantastic.” – Jason Dumont

Protecting and restoring floodplains requires creativity. It means looking differently at areas along streams. Even if you don’t see flooding, could it flood? Should it flood? We have to take the opportunities where we have them to improve and embrace flooding and water on our lands.

- Floodplain: Low-lying land adjacent to a body of water that is susceptible to flooding or prolonged wetness. ↩︎

- Groundwater: Water held underground in the soil or in crevices of rock. ↩︎

- Pollutants: A substance that has negative effects on the environment. ↩︎